1 Basic strucure

BASMOD is a macroeconomic model based on an extended Mundell-Fleming approach with price and wage setting similar to Layard-Nickell. Macroeconomic policy is endogenous in the model, i.e. fiscal and monetary policy reacts to shocks, using model consistent forward-looking expectations. The entire model is not forward-looking. Rather, forward-looking and model consistent expectations are imposed for variables for which this is considered particularly important, such as exchange rates, wages and long term interest rates.

One could think of the model as an IS/LM-Aggregate Demand model with an aggregate supply side allowing prices and wages to sluggishly respond to shocks and restore equilibrium with considerable delay. Rather than starting from microeconomic optimization BASMOD uses the macroeconomic relationships of the Mundell-Fleming type and optimization of individual agents is only implicit.

Models based on explicit optimization – see Smets and Wouters (2004) or Adolfsson et. al. (2004a,b) – tend to focus on the long run steady state and possibly pay less attention to the short run adjustment than is done in BASMOD. Whether macroeconomic models based on explicit optimising behaviour actually performs better in practice is an open question and I think depends very much on the particular details upon which the respective models are built. For instance, parameters derived from micro theory are changed when applied to macro data, possibly due to aggregation[1]. Such problems means that models derived explicitly from microeconomic optimizing behaviour still can be difficult to interpret. Another problem is that big macroeconometric models seldom are “first best” in the sense that it is derived from first principles in every detail. If this is recognised, the model should be viewed in terms of “second best” and it is then more unclear how to view its merits, e.g. in terms of coherency. BASMOD is more loosely related to microeconomic theory, though equations in many instances can be shown to be derived from some microeconomic optimizing behaviour, at least in the long run.

The standard small-scale macroeconomic (textbook) model is extended in various ways:

1) BASMOD is much more detailed.

2) Stabilization policy is endogenous and forward-looking according to rules.

3) Various specifications are refined.

4) The model is fitted to data by econometric estimations and takes account of both long-run equilibrium and short-run adjustments simultaneously. The major effort is on the medium-term properties, i.e. some 1-4 years ahead.

In this section, the model structure is first presented in terms of macroeconomic demand and supply. Secondly, the structure of demand and supply is explained in detail. For further details the reader is referred to the BASMOD Web Site.

Demand and supply

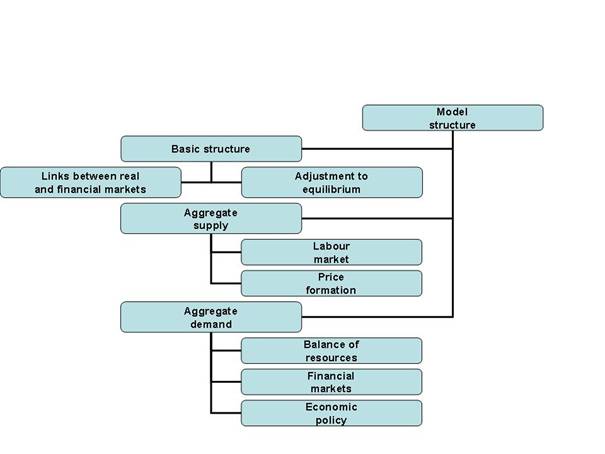

The structure of the model is illustrated schematically in diagram 1.

Diagram

Aggregate demand is a (negative) relationship between GDP and the aggregate price level. An increase in the aggregate price level lowers demand/GDP – i.e. . An increase in the aggregate price level reduces demand through various channels. An increase in the aggregate price level increases the rate of inflation and – given some target inflation rate or for a given stock of money – raises the short-term interest rate. The increase in the short-term interest rate will to some extent also raise long term rates and the exchange rate will appreciate through the open interest rate parity condition. Foreign demand therefore decreases. The increase in interest rates also reduces domestic demand through its impact on asset prices, private wealth and therefore on household consumption expenditure and on Tobin’s Q and therefore on private investments.

Once out of equilibrium it can take quite some time to restore the balance. Various rigidities – such as in prices and wages - explain the delays and the relationships in BASMOD try to take account of this, both in the demand and in the supply side of the model.

Excess demand is the outcome of either an aggregate demand or an aggregate supply shock. In a stable economy or model – such as BASMOD and most other macroeconomic models - some mechanisms should bring the economy back from the state of excess demand into equilibrium. The aggregate supply in the model can be written , i.e. when the price level increases the real wage tend to decline and the demand for labour to increase. This increases output and hence a positive relationship between Y and P. In BASMOD this is accomplished through price and wage adjustment in the labour and product markets that interact in the supply side of the model – through wage-setting and price-setting. Wage-setting is based on a model in which the labour share (in percent of nominal GDP) temporarily is influenced by the rate of unemployment (the business cycle) but in the long run depends on structural factors, such a the replacement ratio. Price-setting is determined by a model for a (representative) monopolistic firm, in which prices are determined as a mark-up on marginal costs. The equilibrium rate of unemployment is established when price-setting is consistent with wage-setting. A key factor in this is the cost function of the firm, since it is from this cost function the demand for labour as well as the marginal cost – which includes labour as well as capital costs - are derived. An implicit assumption is that the wage-setting is such that the real wage rate is set at such a high level that the demand for labour will determine employment. The equilibrium rate of unemployment can be derived analytically but in the model is solved numerically. There is no explicit computation of unemployment or output gaps, though these measures in principle could be estimated. Whereas in many macroeconomic models the output gap and the production function are essential parts and particularly important for price adjustment, this is not the case in BASMOD. Instead the cost function is central and – due to duality – is a sufficient representation of the supply side making output gaps superfluous.

The rigidities in wage- and price-setting interact with other rigidities and determine a complicated short-run dynamics that describe a system that slowly converge towards long-run equilibrium. Diagram 2 shows the forecast of GDP in annual growth rates and levels.

Diagram 2. The forecast of GDP in growth rates and levels. 2004:4 – 2012:4.

It also includes the focus horizon for the Riksbank forecast, i.e. 2004-2006

which is published in the fourth and last Inflation Report of

Important rigidities other than in prices and wages are in investments, the demand for labour and in exports and imports demand. BASMOD tries to capture these rigidities through the parameterization of the model. For instance, the response to a chock in the real exchange rate creates a J-curve in the current balance, which is in accordance with the stylized facts in this particular area. Tobin’s Q investment model is another model based on rigidities which explains the gradual adjustment of business investments in BASMOD.

Diagram 3. The forecast of the consumer price index in growth rates and levels. 2004:4 – 2012:4.

Diagram 3 shows the corresponding figures for the Consumer Price Index. The low growth rates in 2004 are interpreted as temporarily low by the model and it is expected that the rate of inflation will increase from a level about 0.5 percent to its target level 2 percent within one year. The explanation for this forecast is mainly that the main factors explaining current inflation – marginal cost and price adjustment costs – at the moment temporarily have decreased inflation. These factors will adjust towards their long-run values causing inflation to increase.

The mechanisms described so far could possibly stabilise the economy without any help from economic policy. However, the real world contains policy-makers and so does BASMOD. The intention is to describe policy-making reasonably realistic, in which case the model could possibly be used for both policy simulations and forecasts. There is both fiscal and monetary policy and the design of policy is flexible, i.e. easy to change by the model user. Basically, fiscal policy is based on the EU stabilisation pact and stipulates that the government budget deficit on average should be 1.5 percent of GDP, a measure which will be reached with some delay through variations in direct taxes. Monetary policy is a policy rule in which the short term interest rate is set by the central bank and based on the Swedish target of 2 percent rate of inflation. Due to the rigidities and the time delay in the effects of interest rate changes, policy acts on the future expected rate of inflation. Economic policy hence possibly helps stabilise the economy.

Let us now look a little more into the details.